SHOOTING QUEERS AND DYKES

Reductionism in the form of Stereotypical Representations of Homosexuality and Lesbianism has Endured Throughout the History of Cinema. Discuss using examples.

By Matt Micucci

The first Hollywood mainstream film in which two men kissed on screen was Making Love directed by Arthur Hiller and was released in 1982. The film was about a married man coming to terms with his homosexuality. The film, surprisingly didn’t cause such an uproar, and was widely ignored by the critical mass that deemed it a mediocre film.

The first Hollywood mainstream film in which two men kissed on screen was Making Love directed by Arthur Hiller and was released in 1982. The film was about a married man coming to terms with his homosexuality. The film, surprisingly didn’t cause such an uproar, and was widely ignored by the critical mass that deemed it a mediocre film.

It is apparent to this day that that rehearsed and tasteful kiss was a sign of the times, a representation that Hollywood too could no longer ignore the growing public awareness of the gay and lesbian rights movements. This, however, did not mean that their representation would be changed and from this point on they would stop being treated in their respective stereotypes, the gays as queens and the lesbians as dykes.

There is a certain timeline one must consider when analysing representation of homosexuals in films. This timeline is also considered by gay film historian Vito Russo in his book The Celluloid Closet. The first stage takes place from the beginning of commercial cinema, which we can trace as being the 1890’s, to the thirties. This stage also includes what is known as the pre-code era. During this time, homosexuality was treated almost in a comedic way, as an object of laughter. A gay character was a fairy, a nance, a poof, a queer. There was never any indication which would show homosexuality as sexual disorientation. The lesbians, however, tended to be treated as dangerous and sometimes violent people, as we see in the characters played by Marlene Dietrich who play upon their sexuality in films like Blonde Venus (1932) and Morocco (1930). This trademark vision of lesbians is something that will plague their representations in the following years, a trait that will remain more of less unchanged.

The second stage takes place from the thirties to the fifties. This is the time of Will Hays, heavy censorship and the Motion Picture Production Code, which was brought in due to pressures of religious groups, who wanted to stop the spreading of bad influence in cinema. In the production code, homosexuality was listed among the immoral things to be banned from movies, and called a ‘sexual perversion’. As a result of the code, depiction of homosexuality was restricted and treated as almost not existing. This is, however, the time of femme fatales, which carried some character traits in which lesbians had been depicted in the previous decades. This was also the time of the sad young men.

The sad young men were neither androgynous nor playing the signs of the gender. It was rather a kind of character whose relationship to masculinity was more difficult. The figure of the sad young man was used, and in many ways abused, even by the gay romance novels, which were rare in the forties and fifties, but could easily be recognised by the connoisseurs from their covers, which often pictured a softly lit young man with a sad look on his face and head tilted down. On the cinema, this character would be portrayed by icons such as Montgomery Clift and James Dean, whose on-screen interpretations began everlasting speculations about their real life sexual orientations. For instance, in Rebel without a Cause (1955), you may argue that Sal Mineo’s relationship to the character of James Dean may be more than a friendship in Mineo’s eyes. Further evidence of this may be found in the ending, when there’s a hint to Mineo’s final demise being a suicide because he knows he will not be able to challenge Natalie Wood’s love for James Dean. This also ties into the love triangle scheme, which was and still is a way of hiding homosexual tones in a movie.

The third stage takes place from the sixties to the seventies. This was a time which saw the rise of gay and lesbian rights movements. It was also the time which saw the preservation of cinema challenged by the rise in popularity of television. To ensure the cinema an audience, the production code was loosened and eventually replaced by a more subsequent film ratings system, the MPAA in 1968. However, as the history of cinema shows us, the fact that homosexuality could finally be portrayed to a certain extent did not mean that people would be mature enough to accept it. As a result, gays and lesbians were once again reduced to their usual roles as queens and dykes. Furthermore, it seemed as if the loosening of the code had only served the use of portrayal of homosexuality as a danger for society and a threat to the heterosexual human nature. This also explains the rise in popularity of film genres like the lesbian vampire film.

The lesbian vampire film was a kind of exploitation film with roots which trace back to the Joseph Sheridan le Fanu’s novella Carmilla in 1872. It began in 1936, with the film Dracula’s Daughter, which was also released two years after the Motion Picture Production Code had been enforced. There is little doubt that the fact this film was allowed release was because it was a negative exploitation portrayal of lesbians, that even in the marketing was emphasised, with taglines like ‘save the women of London from Dracula’s Daughter’ which could have worked as an anti-lesbian rights movement motto as well as a representation of lesbians as a dangerous species. In the seventies, which is generally accepted as the decade of exploitation films, production of lesbian vampire films increased. These included titles like The Vampire Lovers (1970) and Lust for a Vampire (1971), and other films with titles that didn’t leave much to the imagination. This film genre is still popular to this day and the last mainstream film of the kind to have been released was Lesbian Vampire Killers (2009).

Richard Dyer has an interesting theory about lesbian vampire films. He says that the nature with which lesbians are generally portrayed, as dangerous and threatening, is explored still further in this film genre ‘where sexual power through stealth may be articulated with other aspects of fears and taboos concerning women, including imagery of blood as both sexual juices and menstrual flow’.

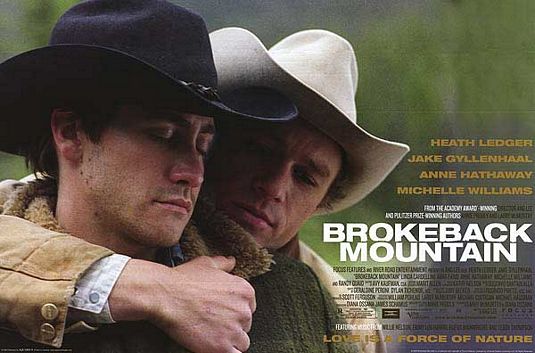

In the same way with which we identify vampires with lesbians, we can identify cowboys with gays. To examine the development of the relationship between the imagery of the cowboy and how it runs parallel to male homosexuality is quite interesting. The two images themselves should represent opposite things, and the fact that filmmakers somewhere along the lines defied that conventional way of looking at them means that somewhere along the line they also tried to defy all that the old Americana ethics stood for. It’s very easy to analyse the history of the cowboy imagery as a metaphor of homosexuality in cinema by analysing three films that have dealt with such a theme. The first is the experimental Andy Warhol film Lonesome Cowboy (1967), the second is the John Schlesinger dramatic film Midnight Cowboy (1969) and the third is the more recent Ang Lee film Brokeback Mountain (2005).

Andy Warhol’s work can be seen as almost avant-garde. Although the filmmaker, as usual, eschews confrontations with any kind of story or clear plot and decides to concentrate more on the various cowboy costume dressing and undressing sequences, the film flirts with the western and the porn feature genres (the western being the genre of the past, the porn feature something that it largely anticipates). The film itself is apolitical, made up of sexual confusion and thoughtless hints to sado-masochism. However it is clearly a product of the sixties, a time of sexual tension, and the time of the sexual revolution.

The minor success the Andy Warhol film had went on to inspire John Schlesinger to make Midnight Cowboy from the 1965 American drama novel of the same name by James Leo Herlihy (he even cast a few of the same cast, most notably Viva). Although this film can be seen as one of the most genuine films portraying homosexuality of the time, it also goes through the pains to avoid suggesting an explicitly sexual relationship between Jon Voight’s and Dustin Hoffmann’s characters. Although they live together and share emotional intimacy, their homosexual nature is always denied, perhaps not only to the audience and the fear of upset normative sexuality, but also to themselves as characters for the exact same fears.

Brokeback Mountain in that sense is a mixture of the two. It is as audacious as the Warhol experimental film, showing an ‘uncomfortable’ sex scene between the two leads and openly dealing with the lead characters sexual tendencies. Building up on that it openly defines the characters homosexual and their story as a genuine exposé of the struggles of a homosexual relationship largely set in the sixties and seventies. Yet, like Midnight Cowboy, it is a melodrama. They share the same kind of ending, where of the two, the most feminine and more expressive character dies, Jake Gyllenhaal is beaten to death and Dustin Hoffmann dies anonymously of an unknown disease on a bus which was to take him and Jon Voight to a better life.

Brokeback Mountain in that sense is a mixture of the two. It is as audacious as the Warhol experimental film, showing an ‘uncomfortable’ sex scene between the two leads and openly dealing with the lead characters sexual tendencies. Building up on that it openly defines the characters homosexual and their story as a genuine exposé of the struggles of a homosexual relationship largely set in the sixties and seventies. Yet, like Midnight Cowboy, it is a melodrama. They share the same kind of ending, where of the two, the most feminine and more expressive character dies, Jake Gyllenhaal is beaten to death and Dustin Hoffmann dies anonymously of an unknown disease on a bus which was to take him and Jon Voight to a better life.

It is inevitable to see the fate of both these endings as a will to leave heterosexuality preserved as the story of the gay characters is once again resolved with another unhappy ending. It seems to be a common fate for the stories which revolve around a type of homosexuals which is referred to as in-between by Richard Dyer, as he says they represent a sexuality that is in between ‘the two genders of the male and the females’. He describes them as the most familiar of gay types, the queen and the dykes, where the male queen is feminine and the female dyke is masculine. In-betweenism never found its representation, as it was often just portrayed in its unpleasantness and ridiculousness. However, representation of gays and lesbians changes considerably with a small movement, at the dawning of the nineties, the last of our stages.

This movement was dubbed New Queer Cinema by critic B. Ruby Rich. The term was initially only supposed to represent a moment more than an actual movement. However, it was clear that a lot of its rise to awareness and eventually popularity was also influenced by two important but not necessarily unrelated things that were taking place around the same time. The first was the survival of the aids virus, which also brought together the lesbian and gay rights movements and organisations that formed new alliances. The second was a revolutionary increase in popularity of small-format video as a medium for both production and distribution. By the late nineties it was estimated that there were around 100 festivals which billed themselves as queer. The films became increasingly popular among the emotionally spent communities of gays and lesbians in need of inspiration.

The movement began more or less, pure. This means that the films were made and often acted, by people who were homosexual themselves or were at least sympathetic to raising homosexual awareness. This was the case with filmmakers like Gus van Sant, and the man regarded as the godfather of New Queer Cinema, Derek Jarman. However, people started to be attracted by the money that these films were making.

What was once an uncomfortable theme to work with and was generally avoided, turned into the opposite. For actors, it could have been a turning point in their careers, for filmmakers, it could have been the chance to make a name for themselves. This was the case with Hillary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry (1999) and Kevin Smith who made Chasing Amy (1997), both of them heterosexual, but one able to give a great award winning performance waking a career that so far had had its highest peak with Beverly Hills 90210, and the other one was able to resurrect a career that had been declining in popularity since the innovative and fresh Clerks (1994). Moreover, a film like Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (1997) brilliantly illustrated the essence of queer romance pointed to the fact that it didn’t matter what your sexual tendencies were, and as B Ruby Rich stated ‘it seemed to be saying it all comes to genius after all, despite of your labels of sexual identity’.

What was once an uncomfortable theme to work with and was generally avoided, turned into the opposite. For actors, it could have been a turning point in their careers, for filmmakers, it could have been the chance to make a name for themselves. This was the case with Hillary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry (1999) and Kevin Smith who made Chasing Amy (1997), both of them heterosexual, but one able to give a great award winning performance waking a career that so far had had its highest peak with Beverly Hills 90210, and the other one was able to resurrect a career that had been declining in popularity since the innovative and fresh Clerks (1994). Moreover, a film like Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (1997) brilliantly illustrated the essence of queer romance pointed to the fact that it didn’t matter what your sexual tendencies were, and as B Ruby Rich stated ‘it seemed to be saying it all comes to genius after all, despite of your labels of sexual identity’.

Finally, homosexuality could be treated as something more than a subject of taboo. In Gods and Monsters (1998), the story of the last days of the homosexual director of Frankenstein James Whale, it seemed natural, thanks to a few small devices that would ensure its success on the mainstream market, especially the inclusion of Brendan Fraser’s homophobic character for the heterosexual audiences to identify with. But for every Gods and Monsters, there were many more films like My Best Friend’s Wedding and The Next Best Thing which were comedies with more potential to reach a more widespread audience that still utilised the same old politics of reductionism to represent the queens as the woman’s best friend, and films like Bound where lesbians were dangerous killers.

In Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (2001) there is even an attempt to a gay male/straight male friendship, which doesn’t seem genuine because characters were altered and some were even added to prevent the gay’s homosexuality from getting in the way of the narrative and the audience’s response to the film. Gigli (2003) did much worse. In the film Jennifer Lopez plays a lesbian who turns straight. Not only did this film manage to anger the lesbian organisations for representing them horribly, it also angered the Christian ones because it promoted bisexuality. For once, both organisations were fighting for the same cause; to get Gigli off the cinema as soon as possible.

These politics of reductionism employed in films are simply done in the best interest of our perception of another word: stereotype. Walter Lippmann, an intellectual writer and reporter, coined the term. He also said that stereotypes ‘are a fortress of our tradition, and behind its defences we can feel ourselves safe in the position we occupy’. This, mixed and supported by the theory of critic Steve Vinberg, who believes that the majority of the audience does not want films to surprise them, tells us why the cinema has never and probably never will stop predominantly showing the lesbians as the dykes and the gays as the queens. After all, even a film that was meant to revolutionise mainstream cinema like Brokeback Mountain had a tragic ending that hinted to a preservation of the heterosexuality, the sexual taste of most of the cinema goers. There is a change, however, in the language of storytelling. In 1982’s Making Love people saw the first gay kiss shared by two less than stellar actors for the first time in a mainstream Hollywood movie. That movie received mixed reviews and now is largely forgotten. In 2005, Brokeback Mountain showed two A-list actors having passionate and violent anal sex. This movie was greeted by a large mixed audience with worldwide enthusiasm.

These politics of reductionism employed in films are simply done in the best interest of our perception of another word: stereotype. Walter Lippmann, an intellectual writer and reporter, coined the term. He also said that stereotypes ‘are a fortress of our tradition, and behind its defences we can feel ourselves safe in the position we occupy’. This, mixed and supported by the theory of critic Steve Vinberg, who believes that the majority of the audience does not want films to surprise them, tells us why the cinema has never and probably never will stop predominantly showing the lesbians as the dykes and the gays as the queens. After all, even a film that was meant to revolutionise mainstream cinema like Brokeback Mountain had a tragic ending that hinted to a preservation of the heterosexuality, the sexual taste of most of the cinema goers. There is a change, however, in the language of storytelling. In 1982’s Making Love people saw the first gay kiss shared by two less than stellar actors for the first time in a mainstream Hollywood movie. That movie received mixed reviews and now is largely forgotten. In 2005, Brokeback Mountain showed two A-list actors having passionate and violent anal sex. This movie was greeted by a large mixed audience with worldwide enthusiasm.