THE NIGHT SILENT STARS TALKED: The story of The Big Broadcast of 1928

It’s implied yet widely never truly acknowledge that the advent of sound in motion pictures was spurred on by the availability and popularity of radio broadcasting.

It’s implied yet widely never truly acknowledge that the advent of sound in motion pictures was spurred on by the availability and popularity of radio broadcasting.

It is generally accepted that radio broadcasting and programming started loosely during the 1920s and moguls such as the Warners had brought in music and other types of variety that had ensured its rise in popularity. Not quite the direct competitor of cinema – as indeed television was destined to become from the late fifties onwards – it was obvious that soon its influence would undoubtedly divulge in the film sector.

This fully materialised with the Al Jolson starring musical The Jazz Singer, an important landmark in film history billed as the first full feature talking movie. There had been numerous sound and vision experiments before it, but with this film 1927 had brought on some revolutionary and somewhat threatening winds of change.

Many actors feared this change, some were aware of the fact that they were not prepared for it. The change famously ended many careers. The great director Cecile B. DeMille described cinema’s rudest awakening in his memoir and the impact it had on its stars by saying “through no fault of their own, they were finished, washed up, out. The gaiety and glitter of Hollywood was theirs no longer. The adoring crowds would soon forget that they had ever lived, the gorgeous homes would pass into the hands of others who had the right voices.” Okay, so in line with the vast majority of his work, this depiction may have been a little exaggerated and over dramatic…

Many actors feared this change, some were aware of the fact that they were not prepared for it. The change famously ended many careers. The great director Cecile B. DeMille described cinema’s rudest awakening in his memoir and the impact it had on its stars by saying “through no fault of their own, they were finished, washed up, out. The gaiety and glitter of Hollywood was theirs no longer. The adoring crowds would soon forget that they had ever lived, the gorgeous homes would pass into the hands of others who had the right voices.” Okay, so in line with the vast majority of his work, this depiction may have been a little exaggerated and over dramatic…

Some actors, in fact some of the biggest stars at the time, aimed to challenge this modern menace and prove to themselves and the world that no change could remove them from the celluloid Olympus. The most drastic example of inspired ‘uprising’ and proud representation took place on a much publicised event which took place on the radio through NBC broadcasting on the 29th of March.

Edgar G. Wilmer, president of Dodge Motors in Detroit prepared the introduce the brand new Standard Six model to the American public, and he would do it on his company’s sponsored show – The Dodge Brothers Hour. This was a show that respected the good old fashioned formats and abided to the audience decency of the time, despite having had some awkward moments in the past. Al Jolson had been a guest on the show and let a ‘rudie’ slip past him what he said that Clara Bow liked to sleep cross ways.

Edgar G. Wilmer, president of Dodge Motors in Detroit prepared the introduce the brand new Standard Six model to the American public, and he would do it on his company’s sponsored show – The Dodge Brothers Hour. This was a show that respected the good old fashioned formats and abided to the audience decency of the time, despite having had some awkward moments in the past. Al Jolson had been a guest on the show and let a ‘rudie’ slip past him what he said that Clara Bow liked to sleep cross ways.

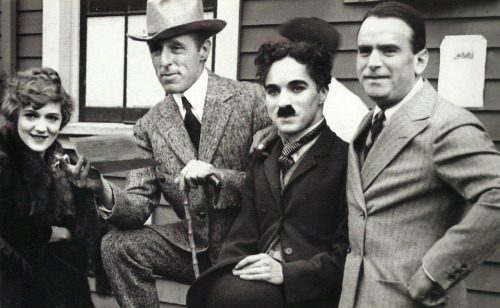

Yet, this would be the biggest one yet. From the United Artists’ studio lot, reportedly for the first time ever, some of the biggest names of the time and in fact of all time in cinema would be speaking to the people. They were Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charles Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, John Barrymore, Norma Talmadge, Dolores Del Rio and Gloria Swanson.

United Artists was an American film studio that was founded in 1919 by D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks with the intention of controlling their own interests rather than having to follow the rules of other big studios.

United Artists was an American film studio that was founded in 1919 by D.W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks with the intention of controlling their own interests rather than having to follow the rules of other big studios.

One cannot emphasise enough the importance and significance of this event, which is often overlooked. Films, were of course, still mostly silent and the vast majority of the biggest names in the industry had done their best to never have their voices heard and especially broadcast for their public to hear. For some it represented a seriously frightening thing that could quite possibly have ended their career.

It is perhaps for this reason that predictably, the giant figures that would speak on this show would abide to the images they portrayed on the big screen. This way, they could also be easily identified.

Yet, given the importance of this event, we can imagine the fear and nervousness experienced by these cinematic gods. So intimidated were they, in fact, that not only were journalists not allowed in the broadcasting room, but neither were any of the studio executives. Even plans to have the show recorded fell through. This sadly means that the show exists only through its chronicling of the time, and not in any audio format whatsoever…

Yet, given the importance of this event, we can imagine the fear and nervousness experienced by these cinematic gods. So intimidated were they, in fact, that not only were journalists not allowed in the broadcasting room, but neither were any of the studio executives. Even plans to have the show recorded fell through. This sadly means that the show exists only through its chronicling of the time, and not in any audio format whatsoever…

Let’s quickly run through the routine. It was estimated that to present his new car model, Mr. Wilmer talked for over half an hour before letting his guests speak. We’ll get back to the repercussions this element of the show had on its reception later…

Starting things off and acting as host, was Douglas Fairbanks. One of the greatest heroic icons of silent adventure films and perhaps the ultimate swashbuckler, Fairbanks was also looked upon as an inspiration, so much so that books were published in his name promoting positive thinking. It was thus suitable for him to address the nation’s youth. He announced in quasi-sacred prose that “it’s not the hardening of the arteries that makes us grow old, but the hardening of our ideas”.

Then came the turn of arguably the most influential director of all time, who unfortunately was also famously bigoted first and then a conscience struggling bigot second (out of this struggle came his masterpiece Intolerance, a film I could personally talk for hours and hours about). As a true old fashioned Victorian, he spoke of love in all its forms – aside of course from its sexual incarnation…

Then came the turn of arguably the most influential director of all time, who unfortunately was also famously bigoted first and then a conscience struggling bigot second (out of this struggle came his masterpiece Intolerance, a film I could personally talk for hours and hours about). As a true old fashioned Victorian, he spoke of love in all its forms – aside of course from its sexual incarnation…

After her came America’s Sweetheart Mary Pickford, one of the female stars of the time that was most appreciated by female audiences. And it was perhaps for this reason that she intimately addressed all the females listening in and reportedly did little more than just that.

John Barrymore followed. Barrymore could be considered the actor most respected by other actors and film people of the time. Coming from a Shakespearean background, he is certainly one of the greatest interpreters in silent cinema. Given his theatrical background, his performance one would expect to have been the most comfortable of the glittering crew and like a true pro, he delivered a soliloquy from Hamlet, probably and predictably the ‘to be or not to be’ one.

Chaplin would never have been accepted as anything else but the clown, and in this broadcast he stuck to telling humorous anecdotes in a funny cockney accent. But even for him, who already at the time enjoyed the reputation as the undisputed genius of comedy and was certainly the figure most highly regarded by critics and audiences alike at the time, this sold him rather badly as a vaudevillian buffoon. In other words, this is far from being his final monologue in The Great Dictator.

Chaplin would never have been accepted as anything else but the clown, and in this broadcast he stuck to telling humorous anecdotes in a funny cockney accent. But even for him, who already at the time enjoyed the reputation as the undisputed genius of comedy and was certainly the figure most highly regarded by critics and audiences alike at the time, this sold him rather badly as a vaudevillian buffoon. In other words, this is far from being his final monologue in The Great Dictator.

Gloria Swanson, who ranks among the greatest symbols of female excellence in celluloid and whose reputation and iconicity matches the likes of Valentino and Garbo, stuck to addressing the female audiences and advising them not to gate crash Hollywood. A somewhat puzzling intervention on many levels.

Next was Norma Talmadge, one of the most popular actresses of the times who – it must be said – was just as good at playing the goody goody heroine (A Tale of Two Cities, 1911) as she was playing the part of the reckless vamp (Camille, 1926). Here, she spoke of fashion and its role in cinema – glamorously expected.

Interesting to note that the exotic Dolores Del Rio, immortal sex symbol of the silver screen and the first Latin American to be recognised as an international and sensational star, chose to sing rather than talk. At the time, her latest flick was being released and she chose to sing its titular ballad ‘Ramona’.

End of the show. Seemingly, everything had run accordingly. Everything had gone as planned. No major issues had interrupted the show and anything awkward had been avoided. Truth be told, it has been said that Fairbanks had cured his mike fright with a couple of glasses of good ol’ whiskey just to calm his nerves, that worked well enough for him to say he didn’t think the broadcast all that much of a big deal anyways…

However, the critical and audience reception did not take long to be viciously voiced. Some audiences had even listened the show live in theatres, a broadcast that had apparently suffered from static and…Mr. Walker’s sermon on the greatness and might of his new set of wheels. Things looked bad! A good summation of the heated reception can be found in the out of print book The Shattered Silents: How the Talkies Came to Stay by Alexander Walker.

“In some small theatres, demonstrations had occurred amongst resentful audiences bored out of their minds by the flood of stilted loquaciousness: occasionally, the loud speakers had to be turned off and admission money hastily refunded. […] Static was so heavy over Buffalo that most of the show was (fortunately) inaudible. In Rochester, Mr. Wilmer’s paean of praise for his new car was greeted with moans and boos. The programme was ‘yanked’ even before Fairbanks’ closing remarks. In Memphis the only star they stood for was Barrymore: the manager reported “they don’t want radio advertising stunts mixed with their entertainment in this burg”. In Detroit, where static caused sniggers, Norma Talmadge was openly cat called. They paid some heed to Fairbanks with his chatter about optimism, but then the hapless Mr. Wilmer spoke again […]”

“In some small theatres, demonstrations had occurred amongst resentful audiences bored out of their minds by the flood of stilted loquaciousness: occasionally, the loud speakers had to be turned off and admission money hastily refunded. […] Static was so heavy over Buffalo that most of the show was (fortunately) inaudible. In Rochester, Mr. Wilmer’s paean of praise for his new car was greeted with moans and boos. The programme was ‘yanked’ even before Fairbanks’ closing remarks. In Memphis the only star they stood for was Barrymore: the manager reported “they don’t want radio advertising stunts mixed with their entertainment in this burg”. In Detroit, where static caused sniggers, Norma Talmadge was openly cat called. They paid some heed to Fairbanks with his chatter about optimism, but then the hapless Mr. Wilmer spoke again […]”

The press was unceremonious in its critical remarks. Poor Chaplin came off the most bruised and battered, targeted as being phoney. His voice, apparently, was not only the shakiest but, worse than all, the only one that seemed shaky! Recalling what his bit on the show was, perhaps he himself hated what he was about to do or at least one would be inclined to think that it certainly did not help.

But what was worse were the rumours, perhaps started by journalists after the resentment at not having been allowed the studio from where the show was broadcast. Two were particularly vicious. The first concerned Del Rio, accused of having been replaced by a trained singer for the sake of the show. This rumour was easily proved unfounded shortly afterwards. The second was Norma Talmadge, and it concerned the same accusation of having been replaced by a voice actress. These accusations were never challenged, and backing them up is poor Norma’s reputation for choking up in public speaking situations.

All in all, it was a disaster. United Artist even hastened to announce that this broadcast was the first and last, never to be repeated again. Furthermore, it was simply a bad omen for the start of the ‘talkies’ era – the most revolutionary era in cinema to date. However, it’s important to note the importance of this event. Firstly, it was spurred out of audience wishes for change. Having had a taste of the talkies, it was expected that from here on in actors would, well, speak! Unfortunately, as an experimentation, this flopped. If anything, it did more damage and good as studio executives were fully ready to resign to the advent of sound and, upon panicking, dismissed the stars of old while theatre players began a mass exodus from Broadway to Hollywood. In some cases, another disaster in its own right due to precipitation - something we will perhaps get into at a later stage.

All in all, it was a disaster. United Artist even hastened to announce that this broadcast was the first and last, never to be repeated again. Furthermore, it was simply a bad omen for the start of the ‘talkies’ era – the most revolutionary era in cinema to date. However, it’s important to note the importance of this event. Firstly, it was spurred out of audience wishes for change. Having had a taste of the talkies, it was expected that from here on in actors would, well, speak! Unfortunately, as an experimentation, this flopped. If anything, it did more damage and good as studio executives were fully ready to resign to the advent of sound and, upon panicking, dismissed the stars of old while theatre players began a mass exodus from Broadway to Hollywood. In some cases, another disaster in its own right due to precipitation - something we will perhaps get into at a later stage.

At a more intimate and informal level, this was mostly the first time the audience could hear their big screen heroes and bring them closer to them. It’s a shame the experience became as wooden and disappointing for them. Variety noted a drop in box office takings for the stars involved in the show that whole year. None, however, were a bigger loser than the hated Mr. Wilmer, as the sales of Dodge cars had dropped thirty million below the figure of 1926!

At a more intimate and informal level, this was mostly the first time the audience could hear their big screen heroes and bring them closer to them. It’s a shame the experience became as wooden and disappointing for them. Variety noted a drop in box office takings for the stars involved in the show that whole year. None, however, were a bigger loser than the hated Mr. Wilmer, as the sales of Dodge cars had dropped thirty million below the figure of 1926!

On the other hand, we must try to understand the pressure felt by Fairbanks, Griffith, Barrymore, Pickford, Talmadge, Swanson, Chaplin and Del Rio. It wouldn’t be fair not to mention how the full introduction of sound affected them and their career.

It would be great to think that after playing the likes of D’Artagnan, Robin Hood and Zorro, he felt he had played all the greatest swashbuckling icons he could and quietly retired. Married to Mary Pickford, a tumultuous and competitive marriage to say the least, his popularity somewhat inexplicably declined. His first talkie, a cinematic version of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (1929) bored Depression-era audiences and he decided to retire completely from acting in 1934. He continued to be marginally involved in the film industry and United Artists, but his later years lacked the intense focus of his film years. He died of a heart attack in 1939, after a long illness.

It would be great to think that after playing the likes of D’Artagnan, Robin Hood and Zorro, he felt he had played all the greatest swashbuckling icons he could and quietly retired. Married to Mary Pickford, a tumultuous and competitive marriage to say the least, his popularity somewhat inexplicably declined. His first talkie, a cinematic version of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (1929) bored Depression-era audiences and he decided to retire completely from acting in 1934. He continued to be marginally involved in the film industry and United Artists, but his later years lacked the intense focus of his film years. He died of a heart attack in 1939, after a long illness.

Mary Pickford’s legacy is one of great importance. She was one of the original 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Known as "America's Sweetheart", "Little Mary" and the "girl with the curls", having to talk also meant having to mature her on screen image and grow up. Unfortunately, this transition took place when she was in her thirties, meaning that the audience had not only already alienated her in the old bubble of silent films, but also refused to accept her as an older woman. Despite her acting abilities, for them there was no Pickford outside of teenage Pickford, and that was a role she could no longer play credibly. She retired from acting in 1933.

Mary Pickford’s legacy is one of great importance. She was one of the original 36 founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Known as "America's Sweetheart", "Little Mary" and the "girl with the curls", having to talk also meant having to mature her on screen image and grow up. Unfortunately, this transition took place when she was in her thirties, meaning that the audience had not only already alienated her in the old bubble of silent films, but also refused to accept her as an older woman. Despite her acting abilities, for them there was no Pickford outside of teenage Pickford, and that was a role she could no longer play credibly. She retired from acting in 1933.

John Barrymore's story is one of the most tragic. A theatrically trained actor, initially it seemed as if the advent of sound would only but add a layer of depth to his performances, and indeed after excellent performances in films such as Moby Dick (1930) and Svengali (1931), odds looked in his favour. But it wasn't the coming of sound that led to his demise. John led to his very own demise. And alcoholic and substance abuser, but the late thirties he was already unfocused and forgetting lines. Despite delivering some admirable performances in later works, his popularity started to decline soon after and his films started to lose money. Harry Brandt printed an article in the Independent Film Journal that deemed him 'box office poison' and a 'dead cat'. By the time he had reached the last years of his life, his works were mostly parodies of himself. He died in a hospital room after collapsing on another live radio broadcast in 1942.

We could talk about Griffith forever. One of the most controversial, genial, revolutionary and deeply conflicted figures in cinema history. His name is synonymous with epics, and his lavish grandiose style, which waned down throughout the years in favour of a more psychological study of his themes could not never have fully adapted itself to the restriction of the new audio friendly technology. In Abraham Lincoln (1930), his first talkie, we see Abraham Lincoln as a version of himself, with an emphasis on his own life struggles of a film industry that was all too eager to get rid of him for good. The Struggle, made a year later, was his final film and ultimate flop. Griffith was discovered unconscious in the lobby at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Los Angeles, where he had been living alone.

Of all the stars in the broadcast, it is very likely that Norma Talmadge is the least remembered. A sad but true tale, despite her impressive body of work that made her so popular and such a reliable lead back in the day. This may be because she was one of the first leading ladies to be alienated from the film industry after being slandered for having a Brooklyn twang. Unfortunately, as it often happens, the rumour was mostly untrue as future radio appearances (of which no conspiracy rumours must be mentioned), reveal this to be a falsehood. On top of that, she lost the support of her sister, who encouraged her to stop trying her luck. On a positive note, she died a wealthy and happily married woman having lived a good life. Norma is simply one of the best examples of quitting while you’re ahead.

Quitting while you’re ahead is something that Swanson aimed to do as well, and in fact mostly did. But she was a phenomenal actress and a clever woman as a whole. Her 1929 film The Trespasser, which followed the disastrous production of Queen Kelly, was filmed as a silent and as a talkie. It was a hit. A couple of years later, she retired from acting and started an inventions and patents company called Multiprizes, which kept her busy and wealthy. But her love affair with the silver screen would re-awaken with her masterful turn as the reclusive silent film star of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. in 1950. A vegetarian and health food advocate, she lived to be 84 after a fulfilling life and career in film but also in theatre, television, as a writer and as an entrepreneur.

Quitting while you’re ahead is something that Swanson aimed to do as well, and in fact mostly did. But she was a phenomenal actress and a clever woman as a whole. Her 1929 film The Trespasser, which followed the disastrous production of Queen Kelly, was filmed as a silent and as a talkie. It was a hit. A couple of years later, she retired from acting and started an inventions and patents company called Multiprizes, which kept her busy and wealthy. But her love affair with the silver screen would re-awaken with her masterful turn as the reclusive silent film star of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. in 1950. A vegetarian and health food advocate, she lived to be 84 after a fulfilling life and career in film but also in theatre, television, as a writer and as an entrepreneur.

Dolores Del Rio distinguished herself as the female version of Valentino. Had he not died before his time, it would have been amazing to have seen them together. A beauty among beauties, after becoming a Hollywood icon, she decided to do the unthinkable – leave America and return to Mexico where she became one of its important figures during its golden years. There, her career flourished and she remained untouched from the threat of a declining popularity that would probably have scarred her had she stayed in Hollywood despite her status as a wonderful actress and amazing singer.

From tragedy to triumph we end on the most positive note. Chaplin’s voice may have been the shakiest during the broadcast, but today he is rightly known as one of the world’s greatest cinematic figures of all time. And while he kept up his wonderful, poetic and hilarious slapstick up to as late as 1936, he provided the most perfect send off for his Tramp persona, as he romantically walked him off into the sunset and handed him to cinema history. And when it came time to speak, he returned in 1940 with one of the most audacious films and perfect use of satire the big screen ever saw. In The Great Dictator he played two roles convincingly, and even worded one of the most loved monologues of all time in his final speech. Loved by one and loved by all, his credibility as an actor only increased when he started speaking. And his choice to make lesser films seemed to be more out of respect for his art and a wish to start a family more than fear of failure.

From tragedy to triumph we end on the most positive note. Chaplin’s voice may have been the shakiest during the broadcast, but today he is rightly known as one of the world’s greatest cinematic figures of all time. And while he kept up his wonderful, poetic and hilarious slapstick up to as late as 1936, he provided the most perfect send off for his Tramp persona, as he romantically walked him off into the sunset and handed him to cinema history. And when it came time to speak, he returned in 1940 with one of the most audacious films and perfect use of satire the big screen ever saw. In The Great Dictator he played two roles convincingly, and even worded one of the most loved monologues of all time in his final speech. Loved by one and loved by all, his credibility as an actor only increased when he started speaking. And his choice to make lesser films seemed to be more out of respect for his art and a wish to start a family more than fear of failure.

(There’s a film in there somewhere, too)