THE GREAT GATSBY by Baz Luhrmann

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s most acknowledged work is also one of the most celebrated American novels of the twentieth century. Its legacy is so strong that one would be forgiven for thinking that The Great Gatsby played a crucial role in creating people’s perception of the social extravagance of the United States of the roaring twenties. On the other side of the Great Depression, in retrospective, everything seemed to be done at an excess – the parties were huge, the bands were ‘big bands’, and everyone always ‘drank too much’. All this extravagance is visually accompanied by the art deco of bold geometrical shapes and over-the-top ornamentations, the Coco Chanel elegance of the flappers, the sparkling crystal chandeliers, giant spiral staircases and two prevailing colours (or non-colours), the black and the white.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s most acknowledged work is also one of the most celebrated American novels of the twentieth century. Its legacy is so strong that one would be forgiven for thinking that The Great Gatsby played a crucial role in creating people’s perception of the social extravagance of the United States of the roaring twenties. On the other side of the Great Depression, in retrospective, everything seemed to be done at an excess – the parties were huge, the bands were ‘big bands’, and everyone always ‘drank too much’. All this extravagance is visually accompanied by the art deco of bold geometrical shapes and over-the-top ornamentations, the Coco Chanel elegance of the flappers, the sparkling crystal chandeliers, giant spiral staircases and two prevailing colours (or non-colours), the black and the white.

It’s no wonder hence that The Great Gatsby and its grand atmosphere would attract the man behind such cinematic follies as Moulin Rouge and the modernisation of Romeo and Juliet; Fitzgerald’s seminal work certainly agrees with the filmmaker’s nature more than other classics like, for example, Wuthering Heights or Crime and Punishment, materials where it would have been much harder to extrapolate such lavish spectacles. Nevertheless, Luhrmann’s choice of sticking to his old ways without branching into unfamiliar dark territories is understandable; why change something that, Australia aside, worked so well in his red curtain trilogy with audiences and critics? It must be said that such success could have been affected by both parties being slightly inebriated by the sheer grandeur of the visual spectacle, too eccentric and trendy to be ignored and not be admired. Yet, there was a darker aura of anticipation and doubt surrounding his latest work. How would Luhrmann be able to keep impressing his viewers in such an overwhelming way, particularly considering his last film’s flop? How would the Australian filmmaker prevent his creative vein from coming across as tiring and, worse of all, yesterday’s news?

For starters, Luhrmann decided to address these issues by exploiting 3D, a predictable choice considering his style. These days 3D feels more and more like the average big production’s easy but pricey way out of having to actually ‘think’ and ‘be creative’, and an easy draw for big box office returns. That is, after all, what seems to be this film’s main concern: to be an extremely popular alternative to the comic book blockbusters which usually take over multiplexes around the summer season. In fact one could argue that this feels more like a comic book movie than a faithful and thought provoking big screen rendition of a classic novel. The big paradox here is that in this way, Luhrmann is brought closer to the novel’s author, who spent the latter part of his career in the movie business trying to write that big hit that never did come in the end. Furthermore, as illustrated in this semi-autobiographical novel, Fitzgerald was always dying to be popular.

For starters, Luhrmann decided to address these issues by exploiting 3D, a predictable choice considering his style. These days 3D feels more and more like the average big production’s easy but pricey way out of having to actually ‘think’ and ‘be creative’, and an easy draw for big box office returns. That is, after all, what seems to be this film’s main concern: to be an extremely popular alternative to the comic book blockbusters which usually take over multiplexes around the summer season. In fact one could argue that this feels more like a comic book movie than a faithful and thought provoking big screen rendition of a classic novel. The big paradox here is that in this way, Luhrmann is brought closer to the novel’s author, who spent the latter part of his career in the movie business trying to write that big hit that never did come in the end. Furthermore, as illustrated in this semi-autobiographical novel, Fitzgerald was always dying to be popular.

Fitzgerald’s alter ego, Nick Carraway, is the voice of the novel and the film. He is a young man who upon moving to New York from the U.S. Midwest is lured by the social scene and becomes the mediator between his cousin Daisy and this almost mystical, mesmerizing and fascinatingly wealthy magnate, Jay Gatsby. For virtually the whole duration of the film we’re left to wonder why such a fascinating man as Gatsby would so desperately try to impress and literally melt in front of an unprincipled and more than slightly ignorant woman like Daisy, but that’s okay, because in that sense it more or less stays true to the novel. After all, this should not be a film about a romance, but rather a film about a romantic guy, who hosts these gigantic parties which attract a whole city in the hope that one day his one true love will wonder in, even just out of curiosity.

In this sense, the film is perfectly comfortable in being just that, and builds up the character of Jay Gatsby as the most charming of romancers. His entrance on the screen is at once cheesy and fully representational of the director’s brand of over indulgence. A close up, a smile and, as the orchestra booms Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, fireworks gloriously explode in the background, filling a wonderful night sky with colour and flair. It’s almost impossible not to fall for the incredible allure of such an entrance, which clocks in after a good half hour, and culminates with that one warm smile carefully highlighted by Carraway’s own narration. That is the kind of smile and charm which Di Caprio has worked so hard to conceal since his days as a teen idol, a reputation he was forced to endure following his performance in Titanic, and a reputation which he has desperately and successfully shake off by leaning towards roles of rough and tough characters, or psychologically disturbed ones in a trend that arguably started with the multiple personalities of Frank Abangale jr. in Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can to the latest stubborn and villainous Calvin Candie in Tarantino’s Django Unchained which was released earlier this year. In The Great Gatsby, Di Caprio lets loose a certain side of his that can’t help but remind one of his plain romantic warmth and charm which was the key to his performance as Jack Dawson in James Cameron’s worldwide box office hit.

In this sense, the film is perfectly comfortable in being just that, and builds up the character of Jay Gatsby as the most charming of romancers. His entrance on the screen is at once cheesy and fully representational of the director’s brand of over indulgence. A close up, a smile and, as the orchestra booms Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, fireworks gloriously explode in the background, filling a wonderful night sky with colour and flair. It’s almost impossible not to fall for the incredible allure of such an entrance, which clocks in after a good half hour, and culminates with that one warm smile carefully highlighted by Carraway’s own narration. That is the kind of smile and charm which Di Caprio has worked so hard to conceal since his days as a teen idol, a reputation he was forced to endure following his performance in Titanic, and a reputation which he has desperately and successfully shake off by leaning towards roles of rough and tough characters, or psychologically disturbed ones in a trend that arguably started with the multiple personalities of Frank Abangale jr. in Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can to the latest stubborn and villainous Calvin Candie in Tarantino’s Django Unchained which was released earlier this year. In The Great Gatsby, Di Caprio lets loose a certain side of his that can’t help but remind one of his plain romantic warmth and charm which was the key to his performance as Jack Dawson in James Cameron’s worldwide box office hit.

There is one pivotal instance, however, where he loses that charm momentarily, revealing his character’s darker side. In that moment, set in the expensive room of a hotel at a private gathering of great importance to the storyline, he seems to feel helpless as Daisy’s husband Tom Buchanan accuses him of being nothing but a hoodlum and frustrated at Daisy’s own inability of telling her husband that she has never loved him. As his grand vision of love crumbles before his eyes, he suddenly turns on Buchanan with the face of someone who killed a man, as Carraway narrates. However, this scene which should have been memorable shows all the film’s main weaknesses in a handful of minutes. Through its unbearable lack of tension and urgency, we finally come to the realisation that the character development has been terribly overlooked.

During the course of every year, we have come to terms with witnessing such blatant examples of style over substance. To bring up such a statement in the review of a Baz Luhrmann production seems a little too obvious, yet the melodrama that laid beneath the frills and feathers of Moulin Rouge was heart wrenching and passionate in its simplicity, not to mention that the re-invention of Romeo + Juliet was tastefully true to the original text and a times felt close to genial. However, The Great Gatsby is overcome by such naivety that make it a clear example of why frills and feathers are not enough, no matter how aggressively appealing the visual aspects are. The characters in this film are dull and toned down in a favour of a Jay Gatsby heavy representation. Yet, it’s inconceivable to expect any true emotional investment in characters who just seem to be, and nothing more.

During the course of every year, we have come to terms with witnessing such blatant examples of style over substance. To bring up such a statement in the review of a Baz Luhrmann production seems a little too obvious, yet the melodrama that laid beneath the frills and feathers of Moulin Rouge was heart wrenching and passionate in its simplicity, not to mention that the re-invention of Romeo + Juliet was tastefully true to the original text and a times felt close to genial. However, The Great Gatsby is overcome by such naivety that make it a clear example of why frills and feathers are not enough, no matter how aggressively appealing the visual aspects are. The characters in this film are dull and toned down in a favour of a Jay Gatsby heavy representation. Yet, it’s inconceivable to expect any true emotional investment in characters who just seem to be, and nothing more.

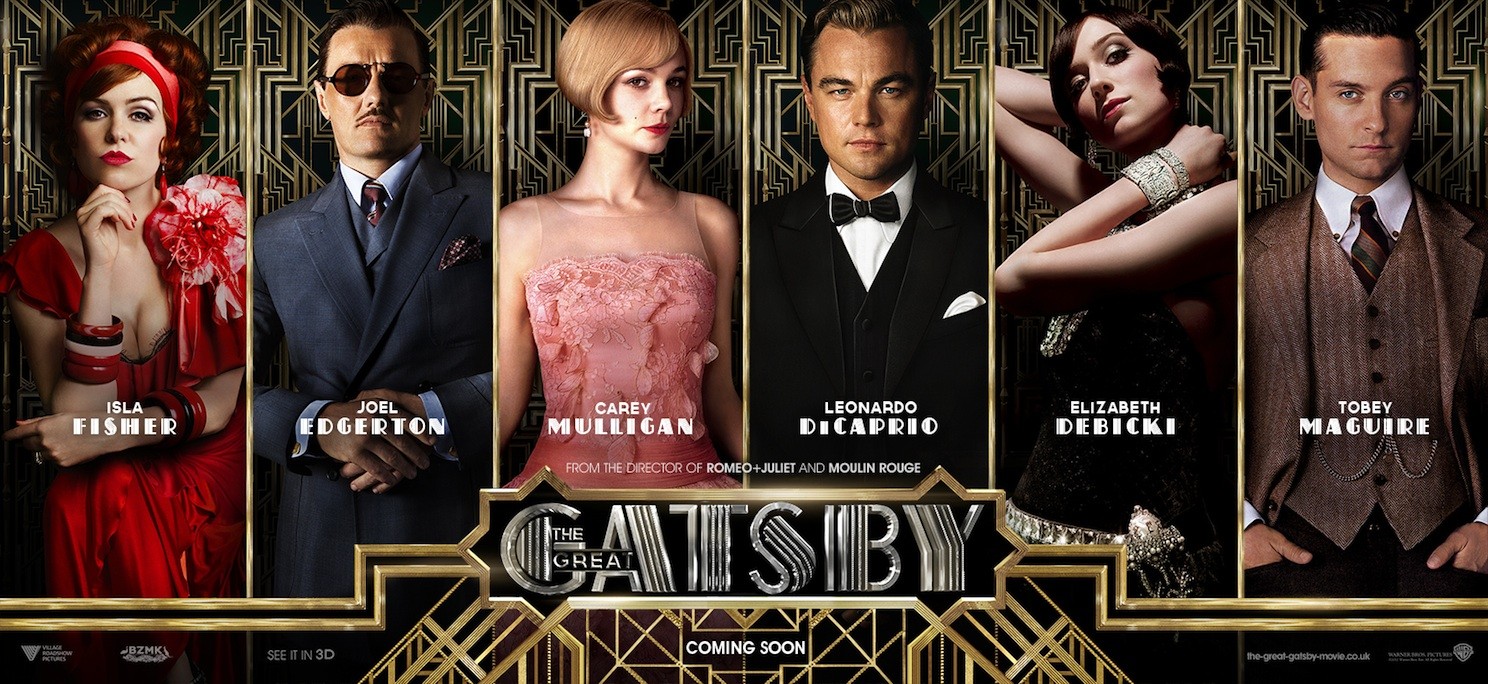

Carraway for instance, the man who provides the voice of the film and the direct link to F. Scott Fitzgerald is terribly overlooked. In spite of some very inspired casting, and a candid Tobey Maguire performance, we know very little about him and his commitment to Gatsby. In the novel, much like F. Scott Fitzgerald, he is essentially dying to fit into the wealthy and glamorous crowd, and allows himself to be lured by his social life on the summer where he had decided to study and become a great stock broker having already given up his dream of becoming a famous and successful writer. However, right from the beginning of the film, we find him telling the story from a sanatorium getting treatment for his moderate alcoholism. It feels like a very forced element, and quite frankly too indolent; it almost feels as if Luhrmann was eager to fit the tale into a familiar structure, which actually has a lot in common with Moulin Rouge. The narration as a whole is a lethargic element which hits rock bottom as the film reaches its somewhat inevitably underwhelming conclusion, when through the film’s epilogue it pays tribute and starts giving importance to Fitzgerald’s original text in highlighting some of the words and quotes from the novel by having them pop up on the screen. If this is a way to legitimise the film, it’s much too little much too late.

Tom Buchanan, played by Joel Edgerton, is supposed to be Gatsby’s strongest antagonist, but his act is weakened by his an alpha male stereotype which makes him seem like a weak comic book villain adapted to a 1920’s melodrama. The story of his affair with the wife of a garage owner, played by Isla Fisher, is treated so insignificantly that it’s hard to believe it would play such a big part in the film’s final act. Carey Mulligan, as Daisy, turns in as lukewarm a performance as they come, and the lack of a strong female presence disagrees with the way in which the film is built up. It’s not, however, Mulligan’s fault that Daisy, much like her husband, goes from being hopelessly in love with Gatsby one moment to not being hopelessly in love with Gatsby the next. The flashbacks make their affair seem even more puzzling and unbalanced, if not downright confusing. Luhrmann, it seems, is more concerned with making the party scenes look majestic than letting us understand whether the central love story is true or just frivolous to Daisy.

Tom Buchanan, played by Joel Edgerton, is supposed to be Gatsby’s strongest antagonist, but his act is weakened by his an alpha male stereotype which makes him seem like a weak comic book villain adapted to a 1920’s melodrama. The story of his affair with the wife of a garage owner, played by Isla Fisher, is treated so insignificantly that it’s hard to believe it would play such a big part in the film’s final act. Carey Mulligan, as Daisy, turns in as lukewarm a performance as they come, and the lack of a strong female presence disagrees with the way in which the film is built up. It’s not, however, Mulligan’s fault that Daisy, much like her husband, goes from being hopelessly in love with Gatsby one moment to not being hopelessly in love with Gatsby the next. The flashbacks make their affair seem even more puzzling and unbalanced, if not downright confusing. Luhrmann, it seems, is more concerned with making the party scenes look majestic than letting us understand whether the central love story is true or just frivolous to Daisy.

For entertainment purposes, The Great Gatsby is also given improbable car chases in antique costume made coupés, perhaps to prevent the average male demographic in attendance from falling asleep. The breezy editing is arguably one of the worst seen in a while. Breezy and unpredictable, possibly to comply with the 3D technique, it sometimes makes the film look clumsy. One sequence comes to mind, when Carraway first meets his cousin on screen, in a living room with curtains flying about due to a draft coming from the back door. The cuts and alteration of the film’s speed are almost embarrassing, as well as the use of shots of daisy fiddling with her fingers or her friend Ms. Baker standing up and stretching in a comical way – it’s the kind of sequence one would expect to be filled with cartoonish sounds outrageously highlighting every motion. Perhaps the feeling was that this scene wasn’t exciting enough as it was, but the truth is that times like these make one realise how precious those moments of cinematic simplicity are.

One aspect of the film which certainly deserves praise is the score, which gathered a lot of publicity when news leaked that it would be executive produced by hip hop artist Jay-Z. Giving up that distinctive prohibition jazz and swing sound seemed in line with Luhrmann’s usual eccentricities, considering the post-modernist mix of the music of his previous works, but it may nevertheless have raised a few eyebrows. Thankfully, the score not only conveys the extravagance of the visuals to perfection, but is also tasteful with its mixture of pop music with the more conventional sounds of the twenties, while Lana del Rey’s ‘Young and Beautiful’ song draws up another parallel with James Cameron’s Titanic, recalling the weeping drawl of one of the biggest hits of the nineties, so famous that it doesn’t need to be named.

One aspect of the film which certainly deserves praise is the score, which gathered a lot of publicity when news leaked that it would be executive produced by hip hop artist Jay-Z. Giving up that distinctive prohibition jazz and swing sound seemed in line with Luhrmann’s usual eccentricities, considering the post-modernist mix of the music of his previous works, but it may nevertheless have raised a few eyebrows. Thankfully, the score not only conveys the extravagance of the visuals to perfection, but is also tasteful with its mixture of pop music with the more conventional sounds of the twenties, while Lana del Rey’s ‘Young and Beautiful’ song draws up another parallel with James Cameron’s Titanic, recalling the weeping drawl of one of the biggest hits of the nineties, so famous that it doesn’t need to be named.

Redeeming factors can be found in the film’s rare sweet moments. The first meeting between Gatsby and Daisy for instance is very cute; Gatsby’s embarrassment and his fretting over her tea time visit is a delightful moment which shows prominently the man’s vulnerabilities and finally reveals his rather clumsy side. However, it is Carraway and Gatsby who share what is by far the sweetest moment in the film. When Carraway agrees to set up a tea date between him and his cousin, he tells him that he’d be ‘happy to do it’. Gatsby, awkwardly offers him something in return, but Carraway dismisses it by telling him that he is just doing him a favour. Gatsby’s reaction is understated, but we can see he is deeply touched, as this might be the only favour anyone has ever done for him out of kindness.

However, nothing can stop Luhrmann’s film from being highly superficial, and his vision of The Great Gatsby from being one of a long line of praised literary classic that still hasn’t found its ideal on screen rendition. Many films, often from the classic Hollywood period, are praised for their lavish large scale glamorous productions, but only a few of them find a good and classy balance between plots and visuals. This is a balance that Luhrmann is unable to give his film, and its confused screenplay doesn’t look like it was given half as much attention as its amazing sets and spectacular cinematography. The Great Gatsby looks and sounds spectacular, and Luhrmann confirms himself as an amazing cinematic aesthetician, but on a thematic and dramatic aspect it truly is as shallow as they come.